Excerpt:

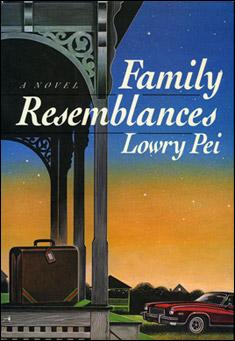

On the hottest days, my Aunt Augusta would drive around New Franklin with the windows rolled up, so that people would think the air conditioning still worked in the Buick she had inherited along with the house. The clear plastic cornucopias on either side of the rear window, which should have poured coolness on the back of our necks, were still quite noticeably there, but the remainder of the apparatus had succumbed to a mysterious illness some time ago. Occasionally, when she got to an out-of-the-way place, she’d hit the four buttons by her left hand and all the windows would slide down at once to let in relief, but she may have done this only when I was with her, to accommodate my weakness and youth; alone, for all I know, she never let down her resolve. She almost managed not to sweat, as if a regal bearing would keep her cool. Once when we were all visiting – my parents and I – my mother, red and hot, told her to her face it was absurd. Augusta, beautiful as she was, looked stony. I could see her in profile from where I sat in the back seat, and I was glad the Buick was big and I didn’t have to be any closer to her. Whose side to be on? There was a silence for half a block, and then she finally looked at my mother and said, “What they don’t know won’t hurt me.”

When I was fifteen and a half I went, or got sent, to visit Augusta by myself because my mother couldn’t put up with me. It was summer again, and I was unbearable because of a lost boyfriend. His name was Roger Andrew, singular; I called him Rodge; he was sixteen, and touched my breasts, which made me feel as if I might die of self-consciousness. Having touched me there and elsewhere a number of times he gradually ceased to call me up, and I became – dramatic. I moped extravagantly, talking on the phone all evening to my best friend Jeanette Markey, sleeping till one o’clock, playing the same 45’s until no one could have made out the words but me. My father seemed nonplussed; this kind of bereavement left him nothing to say, even if I had been willing to listen. Parents like mine didn’t quite admit to themselves that their daughters, even at fifteen, made attempts at sex; but sex was a side issue. There was no talking to me, about that or anything else, so my mother didn’t have to say much when she suggested a thinly disguised exile in the care of Aunt Augusta. In a different mood I might have refused, but I didn’t care what she had planned this time, and I knew that part of her plan, always, was to make it hard to resist.

New Franklin, where Augusta lived, is east of St. Louis in the part of Illinois that did not get flattened out in the last ice age, where “corn” comes out “carn” and people talk about combing their hairs. I rode the train down from Chicago to St. Louis and Augusta made the hour’s drive to pick me up. On the train I wondered if I should have brought a bigger suitcase, to suggest that I wouldn’t mind leaving Evanston for good, or else one that was clearly too small, but no one except me would have noticed. The ride was fast and flat and repetitious – across or down the main streets of small towns so quickly I barely had time to read the signs, and then more cornfields. A couple of times we stopped among the plants that stretched out too far, and I thought how glad I was to be inside where it was air-conditioned. Then another train went by in a long, monotonous rush and we would slide into motion again. I thought about Rodge, about wanting to be touched; desire demanded a good deal of thought. I slouched sideways across two seats and curled into the smaller me that hadn’t yet filled out my body. The upholstery prickled. I was still unhappy, but it was already a relief to know that distance alone would answer the question of why he didn’t call me up, as long as I stayed away. How annoying: my mother had been right again.