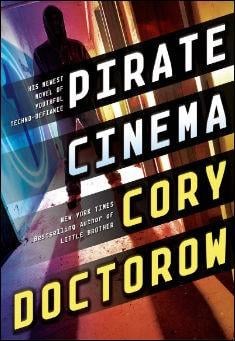

Trent McCauley is sixteen, brilliant, and obsessed with one thing: making movies on his computer by reassembling footage from popular films he downloads from the net. In the dystopian near-future Britain where Trent is growing up, this is more illegal than ever; the punishment for being caught three times is that your entire household’s access to the internet is cut off for a year, with no appeal.

Trent’s too clever for that too happen. Except it does, and it nearly destroys his family. Shamed and shattered, Trent runs away to London, where slowly he learns the ways of staying alive on the streets. This brings him in touch with a demimonde of artists and activists who are trying to fight a new bill that will criminalize even more harmless internet creativity, making felons of millions of British citizens at a stroke.

Things look bad. Parliament is in power of a few wealthy media conglomerates. But the powers-that-be haven’t entirely reckoned with the power of a gripping movie to change people’s minds….

Excerpt from this gripping piece of teen and young adult literature by the great Cory Doctorow himself:

My "adventure" wasn't much fun after that. I was smart enough to find a shelter for runaways run by a church in Shoreditch, and I checked myself in that night, lying and saying I was eighteen. I was worried that they'd send me home if I said I was sixteen. I'm pretty sure the old dear behind the counter knew that I was lying, but she didn't seem to mind. She had a strong Yorkshire accent that managed to be stern and affectionate at the same time.

My bedfellows in the shelter -- all boys, girls were kept in a separate place -- ranged from terrifying to terrified. Some were proper hard men, all gangster talk about knives and beatings and that. Some were even younger looking than me, with haunted eyes and quick flinches whenever anyone spoke too loud. We slept eight to a room, in bunk beds that were barely wide enough to contain my skinny shoulders, and the next day, another old dear let me pick out some clothes and a backpack from mountains of donated stuff. The clothes were actually pretty good. Better, in fact, than the clothes I'd arrived in London wearing; Bradford was a good five years behind the bleeding edge of fashion you saw on the streets of Shoreditch, so these last-year's castoffs were smarter than anything I'd ever owned.

They fed me a tasteless but filling breakfast of porridge and greasy bacon that sat in my stomach like a rock after they kicked me out into the streets. It was 8:00 A.M. and everyone was marching for the tube to go to work, or queuing up for the buses, and it seemed like I was the only one with nowhere to go. I still had about forty pounds in my pocket, but that wouldn't go very far in the posh coffee bars of Shoreditch, where even a black coffee cost three quid. And I didn't have a laptop anymore (every time I thought of my lost video, never to be uploaded to a youtube, gone forever, my heart cramped up in my chest).

I watched the people streaming down into Old Street Station, clattering down the stairs, dodging the men trying to hand them free newspapers (I got one of each to read later), and stepping around the tramps who rattled their cups at them, striving to puncture the goggled, headphoned solitude and impinge upon their consciousness. They were largely unsuccessful.

I thought dismally that I would probably have to join them soon. I had never had a real job and I didn't think the nice people with the posh film companies in Soho were looking to hire a plucky, underage video editor with a thick northern accent and someone else's clothes on his back. How the crapping hell did all those tramps earn a living? Hundreds of people had gone by and not a one of them had given a penny, as far as I could tell.

Then, without warning, they scattered, melting into the crowds and vanishing into the streets. A moment later, a flock of Community Support Police Officers in bright yellow high-visibility vests swaggered out of each of the station's exits, each swiveling slowly so that the cameras around their bodies got a good look at the street.

I sighed and slumped. Begging was hard enough to contemplate. But begging and being on the run from the cops all the time? It was too miserable to even think about.

The PCSOs disappeared into the distance, ducking into the Starbucks or getting on buses, and the tramps trickled back from their hidey holes. A new lad stationed himself at the bottom of the stairwell where I was standing, a huge grin plastered on his face, framed by a three-day beard that was somehow rakish instead of sad. He had a sign drawn on a large sheet of white cardboard, with several things glued or duct-taped to it: a box of kleenex, a pump-handled hand-sanitizer, a tray of breath-mints with a little single-serving lever that dropped one into your hand. Above them was written, in big, friendly graffiti letters, FREE TISSUE/SANITIZER/MINTS -- HELP THE HOMELESS -- FANKS, GUV!, and next to that, a cup that rattled from all the pound coins in it.

As commuters pelted out of the station and headed for the stairs, they'd stop and read his sign, laugh, drop a pound in his cup, take a squirt of sanitizer or a kleenex or a mint (he'd urge them to do if it seemed they were in danger of passing by without helping themselves), laugh again, and head upstairs.

I thought I was being subtle and nearly invisible, skulking at the top of the stairwell and watching, but at the next break in the commuter traffic, he looked square at me and gave me a "Come here" gesture. Caught, I made my way to him. He stuck his hand out.

"Jem," he said. "Gentleman of leisure and lover of fine food and laughter. Pleased to make your acquaintance, guv." He said it in a broad, comic cockney accent and even tugged at an invisible cap brim as he said it. I laughed.

"Trent McCauley," I said. I tried to think of something as cool as "gentleman of leisure" to add, but all I came up with was "Cinema aficionado and inveterate pirate," which sounded a lot better in my head than it did in the London air, but he smiled back at me.

"Trent," he said. "Saw you at the shelter last night. Let me guess. First night, yeah?"

"In the shelter? Yeah."

"In the world, son. Forgive me for saying so, but you have the look of someone who's just got off a bus from the arse end of East Shitshire with a hat full of dreams, a pocketful of hope, and a head full of strawberry jam. Have I got that right?"

I felt a little jet of resentment, but I had to concede the point. "Technically I've been here for two days," I said. "Last night was my first night in the shelter."

He winked. "Spent the first night wandering the glittering streets of London, didn't ya?"

I shook my head. "You certainly seem to know a lot about me."