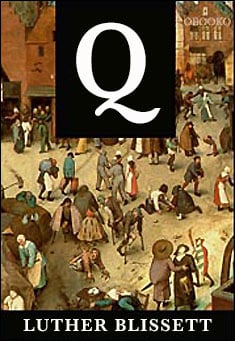

16th Century. Two main characters. One wants to overthrow the social order. The other is a spy in the service of the forces who want to maintain it. Q is the spy, in the pay of Father Carafa, an ultra conservative figure, rapidly rising up the hierarchy of the Catholic church. An epic from the bowels of history, set in central Europe and Northern Italy. Someone described the book as "a theological western". A European bestseller, Q has been compared to Name of the Rose.

The novel Q was written by four Bologna-based members of the LBP, now known as Wu Ming, You may also like to read the Cold War novel, 54 , and Manituana by Wu Ming, both of which are available free on Obooko.

Excerpt:

Letter sent to Rome from the Saxon city of Wittenberg, addressed to Gianpietro Carafa, member of the theological meeting held by His Holiness Leo X, dated 17th May 1518.

To the most illustrious and reverend lord and honourable master Giovanni Pietro Carafa, at the theological meeting held by His Holiness Leo X, in Rome.

My most respected, illustrious and reverend lord and master,Here is Your Lordship’s most faithful servant’s report on what is happening in these remote marshlands, which for a year now appears to have become a focus for all manner of diatribes.

Since the Augustinian monk Martin Luther nailed his notorious theses to the portal of the Cathedral eight months ago, the name of Wittenberg has travelled far and wide, on everyone’s lips. Young students from bordering states are flowing into this town to listen to the preacher’s incredible theories from his own mouth.

In particular, his sermons against the buying and selling of indulgences seem to have enjoyed the greatest success among young minds open to novelty. What was until yesterday something perfectly ordinary and undisputed, the remission of sins in return for a pious donation to the Church, seems today to be criticised by everyone as though it were an unmentionable scandal.

Such sudden fame has made Luther pompous and overbearing; he feels as though he has been entrusted with a supernatural task, and that leads him to risk even more, to go even further.

Indeed yesterday, like every Sunday, preaching from the pulpit on the gospel of the day (the text was John 16, 2: ‘They shall put you out of the synagogues’), he linked the ‘scandal’ of the market in indulgences with another thesis, one which is to my mind even more dangerous.

Luther asserted that one should not be overly frightened of the consequences of an unjust excommunication, because that concerns only external communion with the Church, and not internal communion. Indeed only the latter concerns God’s bond with the faithful, which no man can declare broken, not even the Pope. Furthermore, an unjust excommunication cannot harm the soul, and if it is supported with filial resignation towards the Church, it can even become a precious merit. So if someone is unjustly excommunicated, it can even be seen as a precious merit. So if someone is unjustly excommunicated, he must not deny with words or actions the cause for which he was excommunicated, and must patiently endure the excommunication even if it means dying excommunicated, and not being buried in consecrated ground, because these things are much less important than truth and justice.

Finally he concluded with these words: ‘Blessed be he who dies in an unjust excommunication; because by being subjected to that harsh punishment because of his love of justice, which he will neither deny nor abandon, he shall receive the eternal crown of salvation.’

Uniting the desire to serve you with gratitude for the confidence that You have shown in me, I shall now make so bold as to convey my opinion of the things that I have mentioned above. It seemed clear to Your Most Reverend Lordship’s humble servant that Luther had sniffed the air and smelt his own coming excommunication, just as the fox scents the smell of the hounds. He is already sharpening his doctrinal weapons and seeking allies for the immediate future. In particular, I believe he is seeking the support of his master the Elector Frederick of Saxony, who has not yet publicly disclosed his own state of mind as regards Friar Martin. Not for nothing is he called the Wise. The lord of Saxony continues to employ that skilled intermediary, Spalatin, the court librarian and counsellor, to assess the monk’s intentions. Spalatin is a sly and treacherous character, of whom I gave you a brief description in my last missive.

Your Lordship will have a better understanding than his servant of the disastrous gravity of the thesis put forward by Luther: he wants to strip the Holy See of its greatest bulwark, the weapon of excommunication. And it is also apparent that Luther will never dare to put this thesis of his in writing, since he is aware of the enormity that it represents, and the danger it might present to his own person. So I have thought it opportune to do so myself, so that Your Lordship may have time to take all the precautions he considers necessary to stop this diabolical friar.

Kissing the hand of Your Most Illustrious and Reverend Lordship, I beg that I may never fall from grace with Your Lordship.